40 years is a long time, in a human life. Many are the stories that could be told about any organization that lasted that long, but especially one with the kind of turnover of human lives attendant upon a predominantly volunteer-operated student entity like CKCU-FM. I had the singular privilege of having been a witness to and participant of the birth of that unique institution. Many others share that honour and have their stories to tell, but I offer here the tale of one man’s adventure.

Radio is magic. In the womb I listened while my mother danced. My epiphany came at the age of three, when I found myself sitting on the floor by a heating vent playing with my brother’s toy radio. It was a so-called “crystal” radio in the shape of a 50s-style rocket ship with the antenna in the nose. It had to be grounded so the electrons could flow, the trickle of power from the airwaves enough to vibrate the tiny driver in the ear bud. I had seen others use it, the bud was in my ear, but nothing could be heard. Another wire trailed from the device, ending in an alligator clip, designed to be attached to any metal structural element that would act as ground. I picked up the clip with one hand, studying it, and at the same time shifted my position so the other hand rested on the metal vent, effectively closing the circuit with my body. The unmistakable sensation of the energy traversing me from limb to limb was accompanied by the sudden sound in my ear of the local AM station to which my brother had earlier tuned the radio. Johnny Horton and Paul Anka were big that year, but I like to think the song was Duane Eddy, or maybe one of those wacky space-themed party songs that had been inspired by the launch of Sputnik 1. Whatever it was I had become in that moment genuinely -- and literally -- electrified by: radio, and music (and science fiction).

As a pre-teen I picked discarded radios out of the trash and wired them up with extra speakers and exotic antennae, similarly discarded. I would go to bed surrounded by the wispy wonder of distant voices and exotic rhythms.

In Grade 8 I acquired a little tape machine and a friend and I recorded hours of spontaneously inspired audio theatre, handing the microphone back and forth until the tape ran out, rewinding and listening, then (breathless from laughter), rewinding and recording again. We convinced our teacher to spend a block of one term having the class write and produce radio plays.

As a teen I started a “radio station” in my high school in suburban London, Ontario. They let me wire up speakers in the cafeteria running from the turntable and microphone in the projection booth, and I programmed a stable of deejays to play tunes during 15 lunch periods a week.

A government job brought my family to Ottawa and I took my Qualifying Year at St. Pat’s College on the Carleton campus. I immediately went in search of the “St. Pat’s Radio” which had been mentioned in their promotional material, but which turned out to be an apparently abandoned closet with a bare-bones setup that played music into one study room that was usually unoccupied. But then someone told me about Radio Carleton, and my life changed.

CKCU started in the 60s as a radio club producing weekly programs for an AM station, in the 70s wiring the campus for sound and programming limited hours that could be heard in the tunnels and selected commons areas, then successfully applying for a “carrier current” license that allowed them to place a transmitter on the power grid of the residence buildings. Their studios were in the same location as now, but unlike now I found myself getting off the fifth floor Unicentre elevator to zero security, empty hallways and little signage. I walked in the first door I saw, which at that time happened to be the executive office.

Only one person was there that day, a rather intense-looking black-clad young man reading Rolling Stone with his feet up on a desk. He looked at me. The what do you want? was implied.

I hesitated. Then I said: “I want to do radio plays.”

He hesitated, looking me over. Then he said: “Last door on the right, ask for Eric,” and went back to reading. I later found out this was Peter Lennon, the station manager, an important part of the CKCU story, and someone who would become a good friend.

Last door on the right was the production studio, and Eric Dormer, the production manager, was a bespectacled tower of boyish good humour, all button-down and military haircut. He looked up from what might have been schoolwork. “The guy down the hall sent me here,” I offered before he could ask. “I want to do radio plays.”

He fair leapt to his feet and led me into the room, where the main production equipment dominated the space. “Well let’s get you trained!” he enthused, cheerily.

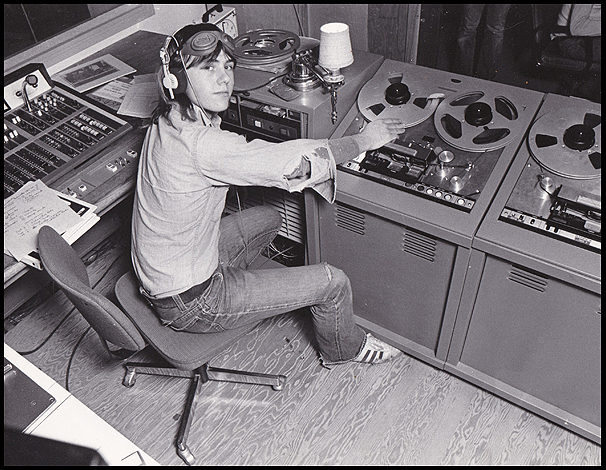

Compared to the gear I had used to this point this multi-input McCurdy rotary-dial board with TWO turntables and THREE Ampex reel-to-reel decks was like the bridge of the Enterprise. It was so astonishing to me that such an array would not be in high demand that I presumed I had lucked into a rare window of opportunity, and in minutes had learned enough to start work. I grabbed a pad of yellow foolscap and started writing, and when I had enough material I ran out into the hall and handed it to the first person that I saw, begging them to read it for me in the studio. Many hours later I was thrilled to find that no one had shown up to kick me out and I had managed to cobble together the first segments for my first production, a bizarre experimental anthology of sketches and notions that I chose to call “Putting In Time On A Blue Star” for no particular reason.

As entertaining as this piece might have been (at least for me), it did not make a splash that I recall, and I found my contributions to the station relegated to recording and editing public lectures and the occasional “on-air” show. In fact I cannot remember if that first piece was ever played on the station at all. History shall not judge its merits as the only copy was accidentally erased in a tape purge some months later.

But things changed for me with Azort Starbolt: Space Android. This was the name of a character that I had invented in high school, the star of a satiric sci-fi fantasy novella that I had written over many months to amuse a couple of friends. I adapted the characters to a comedy short form heavily inspired by Firesign Theatre and Monty Python, and enlisted all of the station’s more colorful characters to play roles. I would write the episode the night before, record it in the afternoon, then while the cast went off to dinner and beers I would edit it together. Then everyone would come back, gather in the studio, and give it a listen. And laugh.

And rewind and listen and laugh again. And do it again. Those were moments I lived for, about as much fun as I’ve ever had. As an afterthought I would put a copy in the on-air studio for a Friday evening playback on the station.

The thing was, it didn’t really feel like anyone was listening. While on air you might get a call or two from a student in residence, but mostly not, and who knew if anyone heard anything in the tunnels or the lounges? We really felt like we were only playing at radio, but it hardly mattered because we were having such a hoot. Many years later I was told by someone who had been in residence at the time that in one of the lounges in the Glengarry Building someone set up a sound system and on Friday evenings there would be a sizable gathering to listen to the latest Azort. That might have been fun to know at the time, but it wouldn’t have made much of a difference. I was already on top of the world. I had found friends.

One of those was Randy Williams, who had succeeded Lennon as station manager, and whom I had called upon for many a role in the Azort saga. He was enjoying himself as well, of course, playing radio, but clearly had a larger vision. I noted he was especially complimentary about the promotional work I did, like the station i.d.s, or an ad for the Student’s Council. I believe it was in the moments he heard those items that the thought crossed his mind that not only was he helming a station that was good enough to attract and keep a real audience, but there was no reason it couldn’t also be a commercial station.

Randy and his cohort, the extraordinary Craig Mackie (who with Lennon and Chief Engineer Paul Munson were the four pillars on which the station was truly built), drafted the FM application, for a commercial license. My contribution to the process did not come until they were preparing for the hearing before the CRTC, at which time I was tasked with producing the prerecorded portion of our presentation. I called upon every resource the station had to offer, attempting to create an effective profile of all its facets, framed in an entertaining package. The final product was, at least, amusing to the eminent authorities at the head table of our hearing in Hamilton, and apparently didn’t hurt the license application, perhaps presenting as it did tangible evidence of a unique collection of enthusiastic people with a genuine capacity to produce entertaining audio. Or maybe it just made them laugh, and that was the nudge they needed to grant the license.

It must be understood that as far as I am aware there had never been, and has never been since, a commercial license granted to a student station in Canada. The arguments against it from the perspective of the commercial broadcasters are many, since the college itself usually supports the station (or, as in the case of Carleton University, the students through a fee managed by the student’s council), and most of the employees are volunteers, all together giving the student station an unfair advantage in a commercial environment.

One key reason for this decision, I believe, was the rather stark landscape of Ottawa radio at that time. The fastest-growing genre in North America in the early-70s was so-called album-oriented rock, which with its longer tracks and more experimental musical forms was electrifying the FM airwaves in most major centers, and it was very much the dominant genre on CKCU (without forgetting the mosaic of ethnic and specialty shows). In Ottawa the only examples could be found in occasional programs on a couple of AM stations while the FM band was the domain of classical and MOR. There could be no argument against unfair competition when there was no competition, so they let us sell ads.

And for a brief wonderful window we were the only game in town for many of the artists that are now inextricably associated with the decade, for those game-changing tracks that are now the staple of the Classic Rock stations that continue to mine that treasure trove. The record reps were calling us, the swag was rolling in, the artists were dropping by for a chat. There was this sort of giddy harnessed fervency, as if some kind of administrative error had accidentally placed a major metropolitan radio station in the hands of a bunch of teenagers… and we certainly weren’t about to squander this windfall for lack of enthusiasm and effort.

It is astonishing to me to realize how brief a time I spent, in fact, at the station, there at the beginning. It is more naturally measured in months than years. I came back in another century and did regular overnight slots for seven years (a friend asked me to come in and help him do a show, then he got tired of the hours and left), and that feels like much less time than I spent in those early-70s hallways. There I found my first home away from home, my first paid job, my first love -- and to have passed those milestones in such a richly creative enterprise with such fun people and with such tangible rewards …

While I was indeed an FM founder, and my efforts were part of the collective which brought about the station’s existence, CKCU is not a child of mine. Mine were not enduring contributions. No mention is ever made, for example, of the conceptual art piece I attempted to make of the station launch. It was in response to a couple of developments: first, we had decided to do it on Hallowe’en, and second, the Carleton Physics Department had gotten some press challenging our right to broadcast based on interference the transmitter was causing in their labs (at that time the transmitter was on the top of the Arts Tower, not at Camp Fortune as now). It was not a great leap to imagine giving the whole thing a Welles-ian slant.

So it was that the station actually first launched (in November, after a delay to work out the physics problem), by running several hours of a loop with an electronic voice saying "Radio... Active" followed at the scheduled hour by a series of dire announcements clearly informing listeners that if they were in the range of our transmitter they were receiving a likely-fatal dose of radiation. Nobody panicked; nor, apparently, noticed (except for Eric Dormer – he loved the idea and ran through the tunnels wearing an authentic radiation suit, yelling at people to take shelter). The official story is that the first sounds on the station were Joni Mitchell’s “Turn Me On I’m A Radio”, which is really dreadfully boring, and cloyingly Canadian, but probably better than the truth.

My other primary contribution was, I believe, much better considered, but no more successful. Part of the message of our license application had been that our advertising would be unlike that on “normal” commercial stations. We were going to have a more flexible attitude towards the promotional content, use experimental techniques, minimize sense of interruption and increase entertainment value, and we presented examples at the hearing. In addition I had instituted a thing called “Wild Carts”, which were prerecorded segments of varying length to be used during a deejay’s shift. These were comedy clips, sampled TV bits, sound effects long and short -- all kinds of things. The idea was that the host could use these as random seasoning; to signal a shift in musical direction, to create an atmosphere for a spontaneous bit of ad lib histrionics, or whatever. I had this vision of a kind of formless flow that was constantly mutating, dreaming in sound. When I did an on-air shift I would sometimes, instead of playing the recorded ad, reproduce it live with actors and effects, turning it into an extended improvised sketch that would change direction and flow into the next program segment.

But only a small percentage of the hosts were even remotely interested in creating some kind of post-radio based on my loopy philosophy, and except for a few isolated examples those I attempted to train in the medium were unable to generate much more than mainstream-sounding advertising, so the experiment was a bust. And then along came CHEZ-FM, which primary founder Harvey Glatt readily admits was created because CKCU had demonstrated there was market for the AOR genre. With ten times the broadcast power CHEZ tangibly stole 93.1’s thunder and (since they were, in fact, competition) successfully challenged their commercial license.

I was no longer at CKCU at that time. Pathetic station politics had seen me ejected from the tribe, but my emotional nadir turned into a blessed renaissance as I was accepted as the first production manager when CHEZ took to the air in 1977. And that was also a lot of fun, but with more money, and more listeners. CHEZ in those early days was very much CKCU on steroids, a significant part of the inspiration, and some of the personnel (like myself), having come directly from there.

But no one forgets the songs that accompanied the passage from youth to adulthood, and nothing will dim for me the glory of the memory of those times at Radio Carleton. There I filed away a thousand great moments, like interviewing Bryan Ferry soon after we went on the air, having him take calls from listeners like it was old hat, slack-jawed station personnel stacked three high in the announcer’s booth to watch. Or the time the Wilson sisters, on their first tour with Heart, flirted with me through that glass.

Only those present at that time can know the specific rush of the founders -- the creative urge made manifest in such a uniquely spectacular fashion -- but in many ways those that have come after are re-experiencing that birth every time they hit the mic switch, or click play, or drop a diamond into a moving microscopic gully of bliss … It is because all of the efforts by people like myself -- people with an idea about how radio should sound -- failed, and what has prevailed, as ever, is the miracle of the programmers.

They are the unique and wonderful voices who have always been drawn there, and they have always come without bidding or at the behest of promotion, the moment they knew that such a place existed, and for no more reward than the process it makes possible. They come with stories to tell, or a depth of music to share, and they already know perfectly well how radio should sound thank you very much. Every further utterance, musical note, and sound effect to be heard on that frequency is the reiterated birth cry of what remains against all odds one of the most truly free mass media outlets that this capital culture has to offer us.

The spirit of CHEZ is long gone to corporate radio, but the mighty 93 still soars along on sturdy wings. I am proud and happy to be part of that story, and Ottawa should be grateful as hell that it’s part of their story, too. |